Inside America’s Oldest Tofu Shop

Opened in 1911, Ota Tofu makes its products following a traditional, time-consuming recipe—but it’s worth the wait.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: If you ever find yourself in Portland, Oregon, in the southeast part of the city, it’s a really nice spot to go and poke around. There are a bunch of cool antique shops, furniture makers, restaurants and bars in big old converted industrial buildings. It’s just a nice neighborhood to kind of go exploring in.

And while you are there walking around, it’s worth keeping your eyes peeled for a low-slung building set a little way back from the street. It’s got a bright red door with a sign in both English and Japanese.

Lauren Yoshiko: You can technically go in. They don’t advertise that really broadly. So you almost feel like, am I allowed to be in here? Because you open up the front door, and this steamy, steamy cloud of warm, damp soy vibes kind of immerses you. And there’s no one at the front desk because everyone’s working. And then you’re like, hello? And they say, yeah, what do you want? And you just do an exchange.

Dylan: This is Ota Tofu. If you live in Portland, you’ve probably seen this brand of tofu at the grocery store. But you can actually get it right at the source, right at Ota’s factory, because this is where they make all of their tofu on-site.

Lauren: They grab it out of the vat, freshly made, put it in a bag, like a goldfish, frankly, with some water in it. Or in a little to-go takeout container. There are a handful of people who are all, it looks like they’re fishermen. They’re in tall boots because water is involved with most of the steps. So everyone’s got like Wellington boots on or whatever you call those and hairnets and the whole shebang. It feels like a little bit of a time jump, a little bit of a time machine, because you can tell like this is an old process.

Dylan: This is an old process, brought over from Japan over a hundred years ago. And today, Ota still does things the old-fashioned way.

I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today’s episode was produced in partnership with Travel Portland. We’re going to Ota, the oldest, longest-running tofu shop in America. And the story of this shop is also the story of a multi-generational family business that is intertwined with the history of Japanese American culture in Oregon. We tell you the surprising story of Ota after this.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: I’ve always had, to be honest, a kind of love-hate relationship with tofu. My wife really likes it and often cooks it, and when it’s good, it’s great. But then, when it’s bad, it’s not, it’s just like it has no flavor to it. But apparently, Ota Tofu is, it’s kind of its own thing. It’s on a very different plane of tofu existence.

Lauren: I think most generic tofu that you can find are, they can have a little bit of a cardboardy taste, where it’s like, you want to dress it up with something else. It’s going to need some other flavors. Ota by itself has a really clean, simple, hard-to-describe flavor.

Dylan: This is Lauren Yoshiko. She’s a food and cannabis writer in Portland. Her family is from the area, and she has been eating Ota since she was a little kid.

Lauren: I grew up outside of Portland, actually. So when we got Ota, it was like a special treat. My mom would be like, Ota is the best.

The traditional Japanese way of eating it is cold, plain, with a little soy sauce and a little chives or grated ginger. When you eat that with any kind of tofu, it’s not always great, but when you eat it with Ota, you can taste the difference. It melts in your mouth. All the flavors really, really stand out, and the texture is soft and smooth and creamy, and it doesn’t need a bunch of other flavors. I think that’s probably the best way to describe it.

Dylan: One of the reasons that Ota has this kind of different flavor is all in the way that it is produced. The shop was founded by two brothers back in 1911, and they brought these techniques with them over from Japan.

It starts basically with soybeans. These soybeans are organic, grown in the Midwest, and then they are soaked for hours and hours, ground up, and then cooked. And this gives you basically soy milk. But then this next kind of transformation starts. The soy milk is then turned into these big, soft tofu curds.

Lauren: So Ota’s tofu is made only with nigari, soy milk, and water, and nigari is a Japanese coagulant extracted from seawater. That’s what’s used to create curds out of the soy milk, and they are really delicate to do it in that gentle way. They simply wouldn’t withstand mass production machines. So the hand-pressing, hand-folding is required for this sort of pure recipe.

Dylan: These curds, like cheese, are stirred and pressed and folded multiple times. And for this tofu, this is all done by hand.

Lauren: And that is why it is so rare. Even in Japan, most people are using mass production machines, not doing it in this style. And that’s what makes Ota incredibly special, that not only is it the only one still doing it this way in America, but it’s one of the only ones doing it globally. It feels very old world in a wonderful way.

Dylan: This is, in fact, a very old-world technique. And it all starts with those two brothers at the beginning of the 1900s.

Lauren: So in the early 1900s, Oregon had an influx of Japanese immigrants because of the anti-Chinese laws that were in place. They started enacting exclusion laws to limit Chinese immigration, but guess what? We still need cheap labor as a country. So the Japanese started moving here in flux to help with timber, to help with canneries.

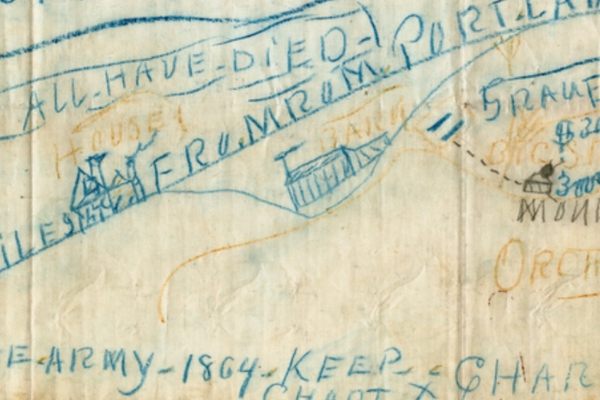

At the time, Heiji and Saizo Ota were a couple of brothers from Okayama, Japan, who set up the first tofu shop in Nihonmachi in 1911. It was originally called Asahi Tofu.

Dylan: Asahi Tofu was part of Nihonmachi, or Japantown. That was a neighborhood in Portland that had a lot of businesses owned by Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans.

And over time, one of the Ota brothers returned to Japan, and the business was kept going by Saizo and his wife, Shina. They renamed the business Ota Tofu, using this anglicized spelling of their last name.

Lauren: Their customer base grew. They were delivering to restaurants around town, and people from the Japantown neighborhood and others came and bought there.

Dylan: Lauren’s own family has a surprisingly long history with Ota. Her great-grandfather owned a corner market in Portland that sold Ota Tofu.

Lauren: And my mom has memories of needing to go down and grab bulk tofu to sell at the store. And so does my grandma. And they talk about going down, and bringing a bin and filling it up and having all this water and bringing it back to sell there.

Dylan: But then everything turned upside down very abruptly in 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the U.S.’s entering of World War II.

Lauren: The bombing of Pearl Harbor was followed by Executive Order 9066, which forced anyone of Japanese descent, whether you were born in the U.S. or not, to go to incarceration camps.

You had three weeks to sell off all of your possessions because you basically didn’t know if you were coming back. You were told, sell everything, you can bring what you can carry, you’re due at this government address at this time. That was the rule.

Dylan: Saizo and Shina sold off whatever they could, but they left Ota’s tofu equipment in the care of their building’s landlord.

Lauren: Saizo and Shina and the rest of the Nihonmachi neighborhood, many of whom went to Minidoka camp in southern Idaho. It’s actually where my great-grandparents went as well. And unfortunately, Saizo did not survive the camps. When Shina returned, the original building owner had been kind and saved their equipment for them, which is a rare story.

Dylan: Most people lost everything. When she returned to Portland, Shina decided to try and pick up where the family had left off, and she began rebuilding this tofu business.

Lauren: It was called the Soybean Cake Company for a while, I think largely because there was so much anti-Japanese sentiment that having any name relating to anything Japanese was scary and negative. And then in the 1950s, they started to feel more confident. They renamed the shop Ota Tofu to its original spelling, O-T-A.

And then, you know, the ’60s and ’70s, things are happening culturally. People are more interested in tofu. Its appeal is expanding beyond Asian communities.

Dylan: And it’s around this point that the associations I have with tofu enter the scene. The hippies arrive. There is this new growing interest in vegetarian cooking and alternatives to meat. By the early 1980s, Ota was ready to expand to a new location.

Lauren: Shina’s grandson, Koichi, started running things with his wife, Eileen. And those two moved the shop to where it stands today on the east side of Portland.

Dylan: Koichi and Eileen ran the shop until 2019. But by that time, they were getting older and starting to slow down.

Lauren: They were like, look, we are tired. This is hard work. We have only so much we can do. And they did not have clear successors in mind. So at that point, they were starting to talk about finding a buyer, shutting it down. And a friend of Eileen’s, Sharon Hirata, said, I think I want to talk to my son about this.

Dylan: His name was Jason Ogata. He is actually a former professional minor league baseball player. And she tried to get him interested in the family business.

Lauren: He wasn’t exactly in the food world. He had a good job in Virginia, was a new dad, he has twins. But his mom was like, look, this is a special place. It can’t die. It has to keep going. And they’re not going to sell to just anybody.

Dylan: He thought, OK, let’s go, Mom. Let’s do it.

Lauren: When Jason was training to take over the business, he went to work with Koichi at 2 a.m. for a year together to learn exactly how it was made. Because Koichi also was like, I’m not leaving until I know you can do it exactly how I did it. And he has since passed, Koichi. So the timing couldn’t have been better for the traditions to be passed on by hand.

Dylan: Jason still gets up at 2 a.m. to start making tofu. And Ota churns out about 4,000 pounds of tofu a day. A lot of that tofu goes to restaurants around Portland, like Tokyo Sando, this popular food truck and now a brick-and-mortar spot, or Murata, this high-end sushi place in town. Of course, you can go and get this tofu right at the Ota store and factory, where it’s just about five bucks a block.

Lauren: It’s the best tofu you can get in the U.S. for $5. It’s so accessible and yet so high-end that the poorest of the college student vegetarians and the highest-brow restauranteurs are both like, of course I know what Ota tofu is. That’s where I go.

It was just a really accessible part of the Japanese American community. And as things have shifted and Portland’s neighborhoods have changed, it’s really something that this place still stands the test of time. It’s still there.

These doors that my mom walked through, my grandma walked through, that I get to walk through and get it for barely more than whatever they paid for it. I feel so grateful to have access to that history just very easily down the street.

Dylan: Go check out Ota’s tofu factory for yourself. They’re open every day except Sundays from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Sponsored by Travel Portland.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook